1970s

Earl Holding’s story started in much the same way Harry Sinclair’s did: with nothing.

Earl Holding was born in 1926. By the time he was 3, his parents lost everything in the 1929 stock market crash.

They managed to stay afloat, however, running a small apartment complex in Salt Lake City, Utah. And Earl, growing up in the thick of the Great Depression, learned about efficiency and hard work early on.

In fact, at age 9 he started doing yard work for his parents’ apartment complex, making 15cents an hour, and saving everything he could. He worked through high school, and by the time he returned from the Army Air Corps in 1944, he’d saved a nice nest egg. He earned a degree in civil engineering from the University of Utah, married his college sweetheart, Carol, and together, they bought a small orchard.

Before becoming Sinclair’s owner, Earl Holding became its biggest customer.

Earl and Carol proved to be an amazing team, with a knack for running things efficiently and earning the trust of their employees and customers. Next, they bought a 10 percent stake in a hotel and gas station in Little America, Wyoming. That one rest stop grew into several; Little America became the highest-volume service station chain in the nation – and Sinclair’s biggest customer.

A friend of Earl’s suggested he buy an oil refinery in Casper. Earl rejected the idea at first, protesting he didn’t know anything about refining oil. But he soon decided to go for it, and started learning everything he could. Within a year, he could talk shop with the best of the engineers, and within five years, he had increased Casper’s output and was supplying fuel for the U.S. Air Force, Union Pacific Railroad and 1,000 service stations in the Mountain West.

In 1968, Holding decided to take things a step further and purchase the assets of the Sinclair Oil Corporation. But in the time it took to reach an agreement with the Federal Trade Commission, the Pan American Sulfur Company (PASCO) swooped in and bought the Sinclair assets first, in 1972.

Four years later, when PASCO decided to sell, Holding and Little America were the first to call.

Meanwhile, the industry was in uproar.

Due to the crude oil shortage, America had grown more dependent on foreign oil over the previous two decades. Then in 1973, the Arab members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) issued an embargo against the United States and several other countries who’d chosen to support Israel in the Arab-Israeli War.

The cost of oil tripled, and several government price control programs further complicated matters. The Holdings had their work cut out for them.

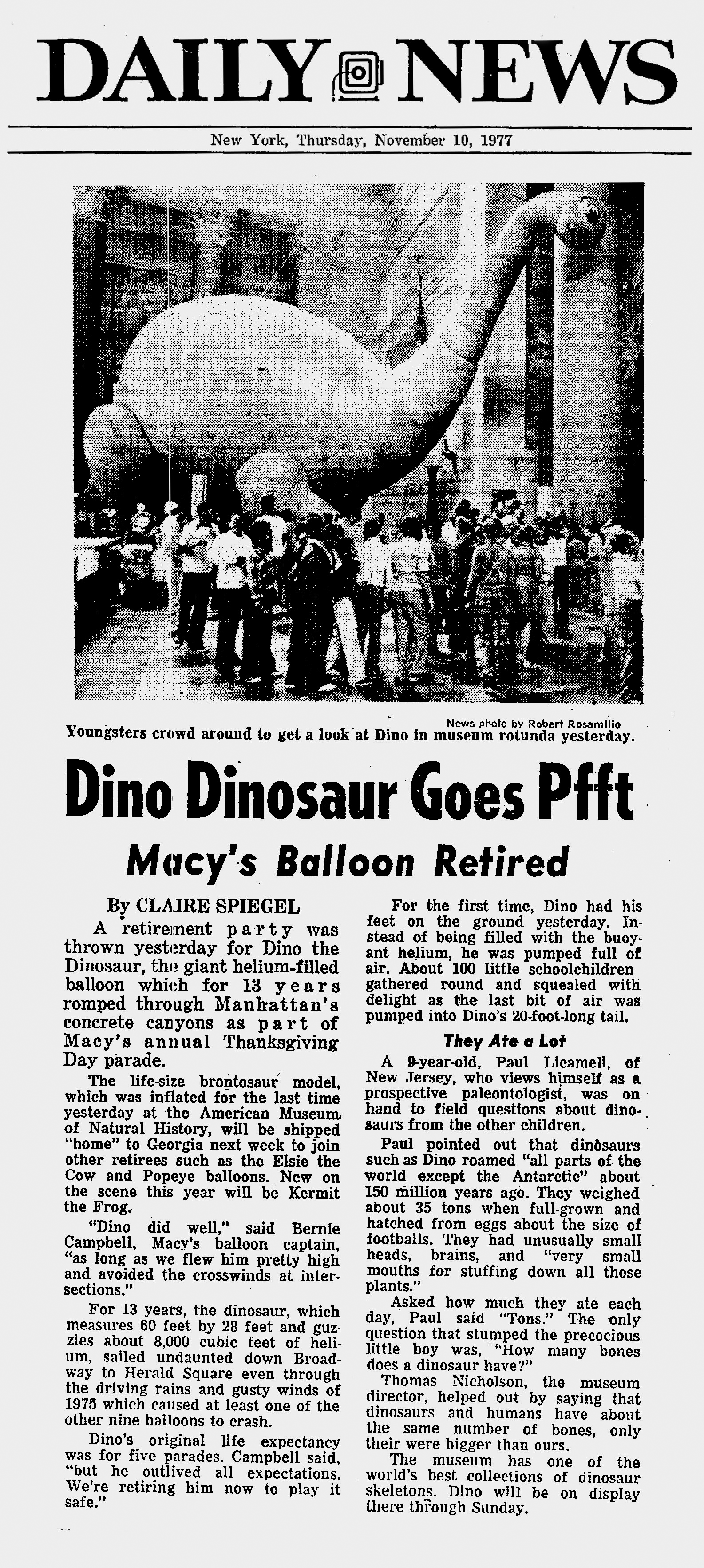

The first Dino balloon retired.

After 13 years in the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade - eight years longer than his projected lifespan - the 60-foot Dino balloon retired from service in 1977. Sinclair showed him one last time at the American Museum of Natural History before shipping him to Georgia to join other balloon retirees. Sinclair returned to the parade with a new Dino balloon in 2015.

Learn more about Dino and the parade.

Then there was the union.

As part of the deal to buy the company, Earl Holding acquired the Sinclair Refinery – which had been unionized since Harry Sinclair had installed it in 1933. The union wanted to run the refinery while Holding and his company simply supervised the administration.

Understandably, Earl didn’t like that idea. He started taking steps toward decertifying the refinery as unionized.

In 1980, there was a strike of refinery workers across more than 100 different companies, including Sinclair. They demanded a $1 wage increase and a certain amount paid monthly toward health insurance. Sinclair already offered full health coverage, and offered to increase wages by 96¢. The Sinclair employees took the deal, and by a vote of more than 60 percent, agreed to deunionize.

It was all thanks to Earl’s integrity.

“The employees learned over a period of time that he would do what he said he would do ... But this was an extremely hard-fought battle … There were shotgun blasts behind the bedrooms of homes where the union felt that the employees were turning against them. This was a very bitter, bitter fight.”

Dale Ensign, the former executive vice president of Sinclair